|

Francis is a Physical Education teacher at Outram Secondary School. He is also the recipient of the President’s Award for Teachers 2020. Francis was instrumental in transforming the school’s water polo team, leading them to the finals in the interschool league in 2011, after their last one 19 years ago.

Trained as a Teacher for Special Needs at NIE, Francis suspected he could be dyslexic and was formally diagnosed six months ago. With the diagnosis, things are coming together for him. He now understands his strengths better and what works for those with special education needs. Working with his fellow teachers, the school implemented study groups where students help each other to learn. This set up has yielded impressive results as the students grew in self-confidence which translated to academic achievements. How did you first find out that you are dyslexic? I was trained as a Teacher for Special Needs. As a lead teacher, I mentor teachers in the school in special education needs. As I delve deeper into this area, I began suspecting I could be dyslexic. I remember reading a book on the strengths of neurodivergent children and saw some of the traits in myself. Six months ago, I went through an assessment at the Dyslexia Association of Singapore which confirmed my suspicion. I wanted a diagnosis so that from a dyslexic's perspective, I can share why some of the teaching pedagogies such as collaborative learning actually works. What was life like as a student prior to your dyslexia diagnosis? I knew I was a slower learner compared to my peers. I started picking up reading only in secondary school and languages were not my strength. My teachers used to call me lazy and my handwriting was untidy. But I did notice that I learn faster than others in certain areas. For example, I was quick at grasping concepts and can see 3D images easily. My secondary school had an after-school study programme where students were divided into smaller groups to help one another learn. That was very helpful for me. I was always stressed about keeping up with my peers in class. Having a group of friends helping each other made the learning environment less pressurising. As I grew older, I developed lower self-esteem. I started reading self-help books as I wanted to build a positive growth mindset. Each time I tried something and failed, I told myself it was another chance for me to try again. As I build up my confidence, I started getting better at what I do, such as playing sports and my studies in the university. What inspired you to become a teacher? I believe that if more teachers form study groups and help the students build self-confidence, more of them would enjoy studying and do better in life. That influenced my decision to be a teacher. As a teacher, I now understand why many students are inattentive in class and I tried different methods to engage them. For example, I formed study groups in my form class and in the water polo CCA I am in charge of. I also encourage the use of peer coaching and collaborative learning with other teachers. This has helped many teachers engage with more students. In my school, more teachers are now using collaborative learning as the main teaching pedagogy. Students are given a problem to solve at the start of the lesson. Through inquiry-based learning, students with special education needs learn better. Tapping on their strengths and helping each other increase their self-efficacy. I am sure you came across many students who struggle with different learning challenges. What words of encouragement do you have for them? As a teacher of 15 years, I see many strengths in students with special education needs. While most of us focus on their failures or weaknesses, they should be recognised for their strengths. Very often, a person with ADHD finds it difficult to focus on boring lectures. They need something that challenges them and I have seen many ADHD students who are good at solving challenging science problems. The slightest of sound could be magnified and bother a person with ASD, but this same trait allows him to spot the small details. Although dyslexics take a longer time to read, we ended up having better understanding and could grasp the concepts. Those students that I know of who are dyslexic had a knack for linking the different concepts together. They definitely make very good peer teachers. Does having a diagnosis make any difference to the way you look at your learning difficulties and is there any positive outcome arising from the diagnosis? As I was diagnosed only six months ago, there hasn’t been many changes. My personal transformation has been a growth mindset and self-belief. I think people who are neurodiverse need to stay positive. It is easy to see ourselves as being inferior to others and give up on ourselves. After my diagnosis, I have a better understanding of the traits I possess. I can see my ability in connecting the different teaching pedagogies and applying them effectively in the classroom. Some parents are still reluctant to send their children for diagnosis for fear of labelling them and putting them at a disadvantage. Now that you are an adult and looking back at your younger days, what are your thoughts on this? Since my diagnosis, I have been able to explain to parents the benefits of being neurodiverse. The world needs people who are innovative, able to see the big picture and are self-directed learners. These are traits commonly present in neurodiverse people. When parents heard this, they are more incline to send their children for assessments. I also share about my own learning difficulties and my strengths with my students. After hearing my experiences, more students are starting to realise their strengths and this helps to boost their confidence. How do you perceive dyslexia now that you are an adult, and do you see dyslexia more as a learning difference rather than a limitation? It is definitely a learning difference. Yes, I do struggle in some areas, but with the help of technology, things are much easier for me compared to before. I have also overcome my limitations by using different strategies such as asking my colleagues for help.

0 Comments

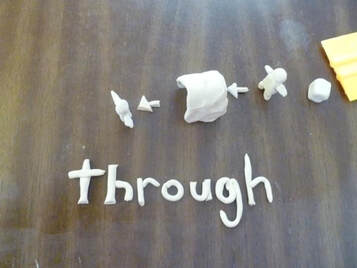

The learning process for dyslexics requires active involvement. Quoting Ron Davis, he said “the creative process and the learning process, if not the same thing, are so closely associated that we will never be able to separate them.” Creativity is therefore an essential part of the learning process. If we create something in the form of memorisation, what we have is something memorised. If we create something in the form of understanding, what we have is understanding. Ron said that if you create something, you can own it. If you can own it, you can experience it. If you can experience it, you can master it, and if you can master it, it becomes part of your thinking process. Try observing your child when he/she is reading. Make a note of the words your child substituted, skipped, inserted, misread or hesitated. Excluding those words your child is unfamiliar with, you will notice that most of the words where mistakes are made are high frequency words such as ‘the’, ‘of’, ‘at’, etc. Being picture thinkers, these words often produce a blank picture for the child whenever he/she comes across it. The child may know how to spell and/or pronounce the word, but because there is no picture representing what the word means, it becomes a source of confusion for him/her. To resolve the confusion, the child needs to ‘create’ for himself/herself the meaning of the words he/she has difficulty using, spelling, reading, writing or understanding. In the Davis approach, we do this through an exercise called Symbol Mastery (see pic). Using plasticine clay as a medium, the child gets to engage his/her creativity in the course of learning and the outcome is that he/she receives a learning experience that is more impactful and permanent compared to memorisation (which many of our kids do) or writing 10 or 20 times in order to learn each spelling word, etc. To draw a parallel of what I mean, no matter how often we watch someone riding a bicycle and read about what needs to be done, the understanding of it won’t keep us from falling over the first time we get on the bike. Mastering riding the bike requires that we get on the bike and experiencing it for ourselves personally. We have to create that experience in the real world in order to master it. Therefore, when dyslexics create the meaning of the word (that causes confusion) in clay, and then add what the word looks like and sounds like, they are doing what is similar to getting on the bike and experiencing the learning for themselves. That is what mastery is and when a word is mastered, it no longer causes confusion for the child and actual learning can then take place. I find the concept of disorientation unique in the understanding of dyslexia.

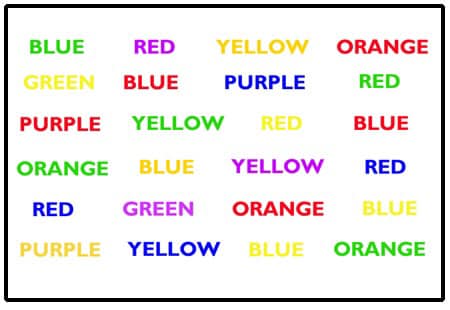

All of us disorientate. We disorientate in order to fall asleep. We disorientate when we day dream. Simply put, disorientation is the mind processing our imagination as though it was reality. Have you ever experienced being in a stationary vehicle, when another vehicle to the front or side of you moved unexpectedly. Suddenly, you felt you were in motion when in fact you remained stationary. Due to the conflict of sensory information that your brain and eyes register, it causes the brain to compromise and distort both perceptions, thereby creating a perceptual illusion. In the case of dyslexia, this natural process of disorientation is triggered by confusions about the identity or meaning of a symbol. As such, the lower the threshold for confusion, the more prone a dyslexic tends to disorientate. In my experience, my daughter’s threshold for confusion is so low that any word taught to her only registered once and the next second, she would disorientate and appear not to have recognised the word just learnt. What then are the signs of disorientations to watch out for? Some of these include omissions or alterations of letters, numbers or words, skipping a line while reading, stopping or hesitating, speeding up or slowing down, frowns or looks confused, concentration intensifies, voice tone becomes monotonous or changes pitch, starting to rock or tap the foot, changes in size of written letters or writing goes off at a slant. To experience what it’s like being disorientated, try the stroop test exercise. First, say the words (eg blue, red, yellow, orange, green, blue, purple, red….) in the box above as fast as you can. Next, say the colour of the words (eg green, purple, yellow, red, yellow, red, blue, green) as fast as you can. Which is easier? How does it make you feel when you try to say the colour of the words (instead of the words) the second time round? I feel my brain a bit “jammed” as it goes back and forth trying to “sort out” the data my eyes see, what my brain is telling me and what my mouth wants to read. It is important to appreciate that during this state of disorientation, information given or learning imparted to a dyslexic can be mis-seen, mis-heard or misinterpreted, which explains why the child mis-reads was for saw, mis-hears the pronunciation of a word, or confuses an explanation given, for example. Following my previous post which talked about a dyslexic’s perceptual talent, it is equally important to understand a dyslexic’s thinking style.

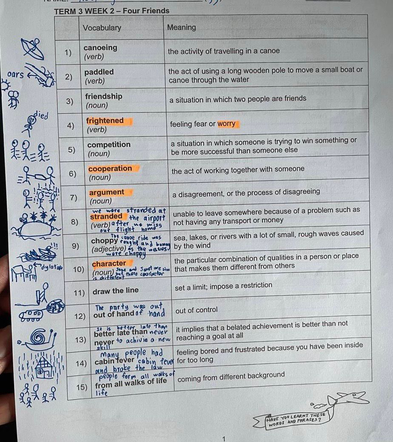

We typically think in 2 ways: word thinking and picture thinking. Word thinking is simply thinking with the sounds of words in your mind. It is a monologue that goes on in your head. I often find myself engaging in word thinking for example, when I rehearse a presentation I’m going to give, or sorting out a problem in my head, etc. Picture thinking, a preference for most dyslexics, is about mental imagery. It is thinking with any of the senses (sound, smell, taste, feeling, visual) in our imagination. A dyslexic chef I once interviewed described how he can mentally picture the taste of a dish he is creating before actually testing it out in reality. When you give direction to someone, we most likely see pictures of where the person needs to go and the pictures then give you the words to say to the person. Dyslexics find it easier to retain information when they see mental images as opposed to words. Try this experiment. Ask your child to draw a couple of random pictures (simple ones and suggest drawing 6 pictures upwards) and write down similar number of random words not related to the pictures. Then get your child to point to each of the drawing and name it, then point to each of the word and say it. Next, ask your child to close his/her eyes and see whether it’s easier for him/her to recall the drawings or the words. This exercise should give you a clue as to whether your child is more of a word or picture thinker. To prove my point further, the picture above is a spelling list shared with me by the parent of a dyslexic boy (who had undergone the Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme). See how he doodled next to the words. By drawing a representation or idea of what the word means, it helped him to attach a visual image to the words. Unlike before where he used to just memorise his spelling words (and even then, not all the words would stick for him), his retention of words has gone up once he understands and knows how to work with his strength (creating mental pictures) rather than weakness (memorising). Dyslexia has been widely viewed as a disability. Parents often commented that their children speak well, seem bright but struggle with simple tasks like reading, spelling and/or writing.

Many do not pay enough attention to a dyslexic’s perceptual talent. This include the ability to see, hear, feel and sense what is imagined as though it was real. Dyslexics can also view and interpret the world in creative and innovative ways. They can also shift their point of perception in order to create mental images, make connections and resolve confusions. That said, how does this perceptual talent also cause learning problems for dyslexics? Seems paradoxical, isn’t it? When dyslexics engage their imagination, they not only see reality, but also creative possibility. Have you looked at clouds (reality) but also see other objects (creative possibility) out of those same clouds? The more powerful the imagination, the more creative possibilities one can see. Applying this understanding, when a dyslexic looks at letters or symbols, he/she could come up with many creative possibilities depending on how powerful the child’s imagination is, and in so doing, the further his/her mind moves away from what the reality is. This in turn results in mistakes during learning tasks. Can you start to see the connection as to how a dyslexic’s talent can also cause learning problems? Outcome is often not proportionate to the effort put in by dyslexics when it comes to learning.

This is such a frustrating situation that even young kids feel it and give up easily at the early stage of learning, if nothing is done to help them. That was my struggle in the initial stage of discovering my daughter’s learning challenges. I had hoped and prayed that she would not give up on herself. What turned the page for me was the shift in perspective in understanding dyslexia. Many today still understand dyslexia as the reason for causing the challenges dyslexics face. One man, however, theorised that confusion (with words, symbols, environment, etc) is what caused the dyslexia. The more confused a dyslexic is, the more the dyslexic symptoms (such as mistakes made when reading) will show. Conversely, the dyslexic symptoms will diminish when the confusion is replaced with certainty. His idea was revolutionary and it answered many of the questions I have when I looked at the many bright but struggling learners I meet, including my daughter. Are you still seeing your child struggling despite the many ways and resources poured in to help your child catch up with his/her learning? Do you find that it’s an uphill task when it comes to completing his/her daily homework? Are both you and your child exhausted from the effort put in just to make that small progress? Perhaps you would like to pick up the book, the Gift of Dyslexia by Ronald D. Davis and consider the Davis approach to tackling your child’s struggles, just like I have. The problem sums featured above are typical of our math curriculum.

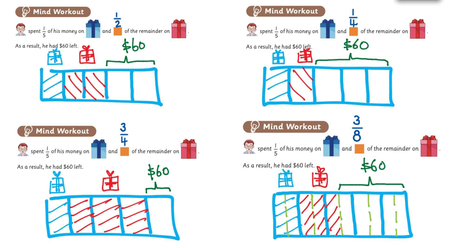

Very often, our dyslexic children struggle to comprehend the questions. There are potential ‘minefields’ in these questions that could set off a chain of confusion for them. You see them re-reading the questions. Frowns start to form, fingers start tapping on the table, they start fidgeting and soon, they throw their hands in the air and exclaim that they do not know how to do the questions. Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. When they encounter certain symbols (be it words or numerals), they get confused by those whose meaning they cannot picture. When they cannot begin to think with that word or concept (such as addition, multiplication, fraction, place value, etc) in picture, they do not know how to make sense of a sentence. In the case of these problem sums, a dyslexic may be confused by the words ‘of’, ‘on’, ‘and’, ‘remainder’ and even concepts of what ‘1/5’, ‘1/2’, ‘1/4’, ‘3/4’, ‘3/8’ mean. Because the child does not know the meaning, he does not know what he needs to do to begin to solve the questions. The first step to help the child is to acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style. The child needs to master not only the meaning of those high frequency words used in math by having a picture or image of what they mean but also be able to picture what the different fractions look like. Very often, a dyslexic child’s struggle with problem sums is not because he does not have the skill to do arithmetic, but because he does not understand what the question is asking of him in the first place, as he cannot think with some of the words or concepts that are in the questions. I first came across the term imposter syndrome about 2 years back. My dyslexic daughter, who was then in her O levels year, had often expressed doubt about her academic abilities.

I had scratched my head numerous times questioning what was she facing that made her doubt herself even though her results showed that she was excelling. I then looked further into the imposter syndrome, a possible explanation for what she is experiencing. This is a psychological phenomena where an individual experiences adverse self-views, which may not accurately reflect what the reality is. Imposterisim can be heightened in dyslexics and other neurodivergents due to the internal stress, worry, anxiety, and fear of thinking and processing differently from others. This brings me to what I felt strongly about. Having your child assessed and applying for exam accommodations are such an important process as it would help your child not only know what he/she is dealing with (be it dyslexia or some other learning difficulties), but also provide him/her with the support they need in order to cope with the worry, stress and anxiety they may be facing. Because my daughter had extra time accommodation, she is able to better deal with her slow processing speed (which is part and parcel of being dyslexic) in a testing environment and give her that chance to at least level the playing field with her peers. As to how to better manage her imposter syndrome, it is still an ongoing journey for me. I recently facilitated a 5 days Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme with an adult dyslexic. Diagnosed in primary school, she received short term intervention then. She is a good reader and spelling is not an issue, but struggles to comprehend what she is reading.

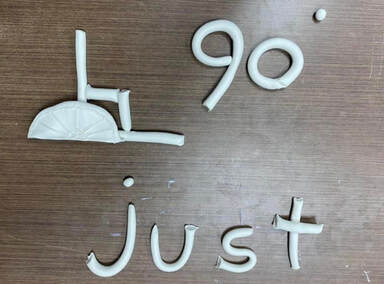

During the programme week, she realised what impacted her comprehension. While she reads fluently, her pace of reading was quite fast and she was not even aware whenever she made reading mistakes. It also dawned on her that she did not have a good understanding of some of the punctuation marks used. Punctuation gives meaning to what we’re reading. The lack of certainty on how each punctuation mark is used and what to do when we come across them (whether to stop, pause, continue reading) added to her confusion. Another thing that struck her was the realisation that she did not really know the meaning of some of the high frequency words (such as by, when, who, which) she encountered in reading. She identified the word “just” as being the most confusing for her and did symbol mastery (see picture below) in order to have clarity of the meaning and that resolved her confusion. “Just” means exactly, precisely. Can you see the meaning in her clay model? The protractor was used to give an exact, precise measurement of the right angle. Once she masters the punctuation marks, resolves any words that caused confusion, slows down when reading and converts what she reads into pictures, she begins to have better comprehension of and retains what she is reading.  Sue Hall is author of the book, Fish Don’t Climb Trees. The inspiration for the title comes from Albert Einstein’s famous quote: “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” The idea behind Sue’s book or Albert Einstein’s quote is that our brains do not all work the same way. Neurodiversity is a viewpoint that acknowledges that brain differences are normal, rather than deficits. Instead of teaching our dyslexic children to learn in a way most neurotypical children learn, let’s accept that dyslexia is a learning difference and work with what our children can do ie their strengths, rather than what they can’t. Hear what Sue has to say in her TEDx Talk here. |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed