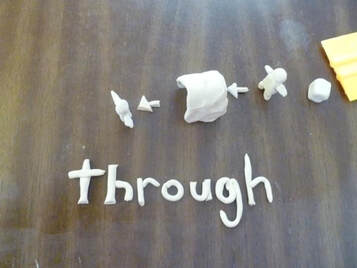

The learning process for dyslexics requires active involvement. Quoting Ron Davis, he said “the creative process and the learning process, if not the same thing, are so closely associated that we will never be able to separate them.” Creativity is therefore an essential part of the learning process. If we create something in the form of memorisation, what we have is something memorised. If we create something in the form of understanding, what we have is understanding. Ron said that if you create something, you can own it. If you can own it, you can experience it. If you can experience it, you can master it, and if you can master it, it becomes part of your thinking process. Try observing your child when he/she is reading. Make a note of the words your child substituted, skipped, inserted, misread or hesitated. Excluding those words your child is unfamiliar with, you will notice that most of the words where mistakes are made are high frequency words such as ‘the’, ‘of’, ‘at’, etc. Being picture thinkers, these words often produce a blank picture for the child whenever he/she comes across it. The child may know how to spell and/or pronounce the word, but because there is no picture representing what the word means, it becomes a source of confusion for him/her. To resolve the confusion, the child needs to ‘create’ for himself/herself the meaning of the words he/she has difficulty using, spelling, reading, writing or understanding. In the Davis approach, we do this through an exercise called Symbol Mastery (see pic). Using plasticine clay as a medium, the child gets to engage his/her creativity in the course of learning and the outcome is that he/she receives a learning experience that is more impactful and permanent compared to memorisation (which many of our kids do) or writing 10 or 20 times in order to learn each spelling word, etc. To draw a parallel of what I mean, no matter how often we watch someone riding a bicycle and read about what needs to be done, the understanding of it won’t keep us from falling over the first time we get on the bike. Mastering riding the bike requires that we get on the bike and experiencing it for ourselves personally. We have to create that experience in the real world in order to master it. Therefore, when dyslexics create the meaning of the word (that causes confusion) in clay, and then add what the word looks like and sounds like, they are doing what is similar to getting on the bike and experiencing the learning for themselves. That is what mastery is and when a word is mastered, it no longer causes confusion for the child and actual learning can then take place.

0 Comments

Following my previous post which talked about a dyslexic’s perceptual talent, it is equally important to understand a dyslexic’s thinking style.

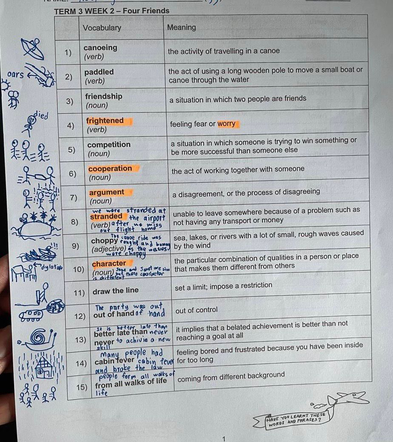

We typically think in 2 ways: word thinking and picture thinking. Word thinking is simply thinking with the sounds of words in your mind. It is a monologue that goes on in your head. I often find myself engaging in word thinking for example, when I rehearse a presentation I’m going to give, or sorting out a problem in my head, etc. Picture thinking, a preference for most dyslexics, is about mental imagery. It is thinking with any of the senses (sound, smell, taste, feeling, visual) in our imagination. A dyslexic chef I once interviewed described how he can mentally picture the taste of a dish he is creating before actually testing it out in reality. When you give direction to someone, we most likely see pictures of where the person needs to go and the pictures then give you the words to say to the person. Dyslexics find it easier to retain information when they see mental images as opposed to words. Try this experiment. Ask your child to draw a couple of random pictures (simple ones and suggest drawing 6 pictures upwards) and write down similar number of random words not related to the pictures. Then get your child to point to each of the drawing and name it, then point to each of the word and say it. Next, ask your child to close his/her eyes and see whether it’s easier for him/her to recall the drawings or the words. This exercise should give you a clue as to whether your child is more of a word or picture thinker. To prove my point further, the picture above is a spelling list shared with me by the parent of a dyslexic boy (who had undergone the Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme). See how he doodled next to the words. By drawing a representation or idea of what the word means, it helped him to attach a visual image to the words. Unlike before where he used to just memorise his spelling words (and even then, not all the words would stick for him), his retention of words has gone up once he understands and knows how to work with his strength (creating mental pictures) rather than weakness (memorising). I recently facilitated a 5 days Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme with an adult dyslexic. Diagnosed in primary school, she received short term intervention then. She is a good reader and spelling is not an issue, but struggles to comprehend what she is reading.

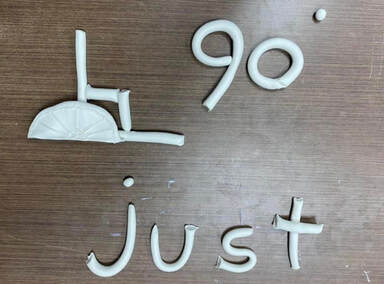

During the programme week, she realised what impacted her comprehension. While she reads fluently, her pace of reading was quite fast and she was not even aware whenever she made reading mistakes. It also dawned on her that she did not have a good understanding of some of the punctuation marks used. Punctuation gives meaning to what we’re reading. The lack of certainty on how each punctuation mark is used and what to do when we come across them (whether to stop, pause, continue reading) added to her confusion. Another thing that struck her was the realisation that she did not really know the meaning of some of the high frequency words (such as by, when, who, which) she encountered in reading. She identified the word “just” as being the most confusing for her and did symbol mastery (see picture below) in order to have clarity of the meaning and that resolved her confusion. “Just” means exactly, precisely. Can you see the meaning in her clay model? The protractor was used to give an exact, precise measurement of the right angle. Once she masters the punctuation marks, resolves any words that caused confusion, slows down when reading and converts what she reads into pictures, she begins to have better comprehension of and retains what she is reading. Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures, as opposed to thinking in words. Very often, they do not have a monologue going on in their heads where they are thinking with the sound of words.

The illustration above would not be too far off from what goes on in a dyslexic’s mind when they are reading. Because of the way they think, whenever they come across words whose meaning they cannot picture, typically the high frequency words, their mental imagery goes blank. A blank picture is the essence of confusion. Having pushed through many of these high frequency words when reading, a dyslexic will eventually reach his threshold for confusion and becomes disoriented. At this point in time, he is no longer getting an accurate perception of the words on the page. When asked what he just read, he will likely give you a variation of what the story is about. If he was reading a comprehension passage, the end result you see is the lack of comprehension, especially when answering implicit questions. To understand dyslexia is to know how it develops, not from the etiology angle, but how it happens functionally. Ron gave us an insight when he identified the 3 factors at work which led to the learning issue.

I have done up the flow chart above which hopefully gives you a clearer picture. It all starts with words/symbols that a dyslexic sees that confuses him. When he is confused enough, he will disorient and start to look from different locations mentally. The disorientation causes perceptual distortion which in turn produces the mistakes which we recognise as dyslexic symptoms. Now that we realise the true nature of a problem, we need a solution, and Ron has developed a 2-pronged approach to correct dyslexia. First off, since disorientation causes perceptual distortion of our senses which then manifests in mistakes, dyslexics need a way to ‘turn off’ their disorientation in order to have accurate perception. To this end, Ron has figured a way for dyslexics to mentally ‘switch off’ that disorientation when it happens, so that the individual will have a stable point of reference when looking at 2-dimensional text. But having accurate perception is not enough. We need to resolve the root cause of confusion. Given that the source of confusion comes from trigger words (which are mostly common sight words), a dyslexic needs to master these words with all its 3 parts, in order for them not to cause any problem for the individual. The 3 parts are (i) what the word means (which will be in the form of a picture to cater to the dyslexic’s picture thinking style), (ii) what it looks like (which is how you spell it) and (iii) what it sounds like (which is how you pronounce the word). A dyslexic may know what a word looks like and sounds like, but if he is missing the picture of what it means or represents, it will produce a blank picture and that adds to the confusion. I like to use the analogy of a headache to simplify the problem/solution explanation above. Before the onset of a headache, one may feel tension building up in the shoulders, parts of the head, etc which we recognise as a symptom. To get rid of it, we typically pop a pill and the pain (symptom) goes away. However, if we do not fix the root cause of the headache (it could be due to life style, posture and so on), we will not be able to eradicate the problem. Applying the same idea, if you address the source of confusion i.e. unrecognised symbols, then confusion will not set in. If there is no confusion, it will not trigger disorientation. If a dyslexic is in an oriented state, you can at this point begin to teach a child to learn and you will notice that the child will register what is being taught. I always joke that there is only one thing consistent about dyslexics and that is, they are consistently inconsistent when it comes to learning. But once the obstacles causing the inconsistency are removed, then easeful learning can take place. The starting point is therefore not to teach a child how to learn (which many are doing by engaging tutors, sending them for enrichment classes and so forth), but to remove what’s preventing their ability to learn. To quote Ron, he said “if you remove the reason why a problem exists....the problem ceases to exist”. It is on this understanding that I put my daughter through the Davis programme and I have not looked back since. In our previous post, we looked at a dyslexic’s picture thinking style and how this can cause confusion for them whenever they encounter words whose meaning they cannot picture. 75% of a page consists of such trigger words and it’s no wonder when they try to read, they would make mistakes.

Today, we’ll look at a dyslexic’s perceptual talent. This is the ability to perceive multi-dimensionally. Simply put, a dyslexic can see an object mentally from many different perspectives, whether by moving their perception to different locations or by mentally manipulating and turning an object, much like rotating a 3D model in a computer to look at its other sides. Matthew, the dyslexic metal fabricator whom I interviewed just before the start of Circuit Breaker, shared that when he was creating a piece of work, he could rotate the end product in different directions in his mind. He would sometimes have an exploded view of the product where he would pull everything apart and then figure out how to fit each piece back together. Another mother whom I spoke with recently also related to me how her dyslexic daughter told her she is able to move her perception to different locations to view an object in her mind. This perceptual talent that a dyslexic possesses allows the individual to think out of the box and to see the big picture. It enhances their performance and is an asset in many occupations such as architects, designers, inventors, scientists, engineers, actors and so on. As with a dyslexic’s picture thinking style, this perceptual talent, while it is a gift, is also a source of learning problem. How so? Let’s hold our thoughts for now until we cover the last factor, and I’ll put the pieces together for you. We have heard of many famous dyslexics such as Albert Einstein, Walt Disney, Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, Lee Kuan Yew, Bill Gates, Tom Cruise, Jamie Oliver, the list goes on. While having dyslexia won’t make every dyslexic a genius, it is definitely good for the self-esteem of all dyslexics to know their minds work in the same way as the minds of these great geniuses. The majority of children could tackle a question like this with ease. However, to those children with dyslexia, they may stumble over such question. Why is that so?

Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. When they encounter certain symbols (and all words are symbols), they get confused by those whose meaning they cannot picture. These are often high frequency words that we use a lot of in the English language, such as ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘by’, ‘to’, etc. When they cannot begin to think with that word in picture, they do not know how to make sense of a sentence. So in the example question above, a dyslexic may be confused by the word ‘from’. The child may be able to recognise and pronounce the word ‘from’ when he sees it, but he does not know the meaning and so he does not know what he needs to do to begin to solve the question. After much drilling and repetition to no avail to help the child understand the question, the child is then told by a well-meaning parent or tutor that whenever he sees such questions, he just needs to take the bigger number and minus the smaller number. By doing so, the child is taught rote learning, rather than have real understanding or true mastery of the subject. If we could acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style, we can help the child master the meaning of ‘from’ and let him create a picture of what it means. According to the American Heritage Children’s Dictionary, ‘from’ means beginning at, starting with. Once the child understands the meaning, he can now picture what the question is asking him to do. Subtract 79 from 139 means that he has to begin at, start with (ie from) 139, and then minus or take away 79, in order to derive at the answer. Visually, he would be able to put 139 down on paper, followed by the minus sign and 79 below 139 and then do his workings to get to the answer. By extension, a dyslexic child very often can’t do problem sums not because he does not have the skill to do arithmetic, but because he does not understand what the question is asking of him in the first place, as he can’t think with some of the words that are in the question. More than 30 years ago, Ron Davis had it figured out that dyslexia is not something complex but rather, it is a compound of simple factors that can be resolved step by step.

He explained that dyslexia is actually a product of a dyslexic’s picture thinking style, their ability to see things 3-dimensionally and their unique way of reacting to the feeling of confusion when they see symbols that they do not recognise (and all words are symbols). Because of these 3 factors at work, dyslexics encounter the difficulties we see in them when learning to read, write and spell. This video illustrates what picture thinking vs word thinking is like and why dyslexics do not seem to recognise the same word which they learnt just seconds ago and as a result, produced mistakes in their reading, writing and spelling. It’s only by understanding this then can we tackle the root of the problem. Ron said that once we remove the reason why a problem exists, the problem ceases to exist. How simple and logical is that? Once I understood Ron’s explanation, I knew instinctively that he had the right solution and I did not hesitate to put my daughter through the Davis intervention programme. We recognise dyslexia by the challenges it presents, but we must not forget its strengths. Dyslexics have the ability to think in pictures, perceive multi-dimensionally (using all senses) and experience thought as reality. They have vivid imaginations and heightened awareness of the environment. They are highly intuitive, insightful and more curious than average. Most importantly, they have the primary ability to alter and create perceptions, which make them very creative people. There are 3 ways people learn - visual, auditory and kinesthetic (tactile). This is different to the 2 thinking styles - pictures or words (or a combination of both).

A dyslexic is primarily a picture thinker, but can be a tactile learner, even though he/she is highly visual, and weak with auditory information. This video, which is created by a dyslexic, shows a dyslexic’s way of thinking (not learning). Knowing how their brain works enables us to work with their strengths, not weaknesses. |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed