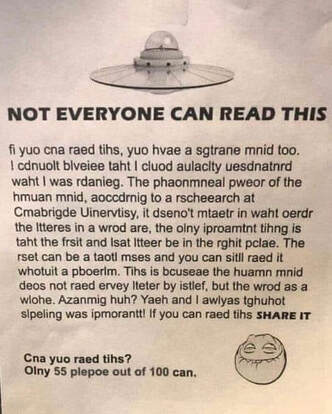

How many of you can read the text easily without having to pause and figure out the sequence of letters in order to make out a recognisable word? One of the symptoms of dyslexia we look for is to observe whether the child is persistently misreading words (such as house for horse, was for saw, etc). Our minds typically scan the whole word (and not every letter of the word) when reading. When in an oriented state, we do not make reading mistakes. However, a dyslexic is easily confused whenever they encounter letters, punctuation marks and high frequency words. Those symbols trigger disorientation which in turn leads to perceptual distortion which results in mistakes. Having accurate perception is important for reading accuracy. A dyslexic’s place of orientation when perceiving a text is often not at the optimal place. Putting oneself in an oriented state is the key to turning off the disorientation and gaining accurate perception.

1 Comment

Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures, as opposed to thinking in words. Very often, they do not have a monologue going on in their heads where they are thinking with the sound of words.

The illustration above would not be too far off from what goes on in a dyslexic’s mind when they are reading. Because of the way they think, whenever they come across words whose meaning they cannot picture, typically the high frequency words, their mental imagery goes blank. A blank picture is the essence of confusion. Having pushed through many of these high frequency words when reading, a dyslexic will eventually reach his threshold for confusion and becomes disoriented. At this point in time, he is no longer getting an accurate perception of the words on the page. When asked what he just read, he will likely give you a variation of what the story is about. If he was reading a comprehension passage, the end result you see is the lack of comprehension, especially when answering implicit questions. To understand dyslexia is to know how it develops, not from the etiology angle, but how it happens functionally. Ron gave us an insight when he identified the 3 factors at work which led to the learning issue.

I have done up the flow chart above which hopefully gives you a clearer picture. It all starts with words/symbols that a dyslexic sees that confuses him. When he is confused enough, he will disorient and start to look from different locations mentally. The disorientation causes perceptual distortion which in turn produces the mistakes which we recognise as dyslexic symptoms. Now that we realise the true nature of a problem, we need a solution, and Ron has developed a 2-pronged approach to correct dyslexia. First off, since disorientation causes perceptual distortion of our senses which then manifests in mistakes, dyslexics need a way to ‘turn off’ their disorientation in order to have accurate perception. To this end, Ron has figured a way for dyslexics to mentally ‘switch off’ that disorientation when it happens, so that the individual will have a stable point of reference when looking at 2-dimensional text. But having accurate perception is not enough. We need to resolve the root cause of confusion. Given that the source of confusion comes from trigger words (which are mostly common sight words), a dyslexic needs to master these words with all its 3 parts, in order for them not to cause any problem for the individual. The 3 parts are (i) what the word means (which will be in the form of a picture to cater to the dyslexic’s picture thinking style), (ii) what it looks like (which is how you spell it) and (iii) what it sounds like (which is how you pronounce the word). A dyslexic may know what a word looks like and sounds like, but if he is missing the picture of what it means or represents, it will produce a blank picture and that adds to the confusion. I like to use the analogy of a headache to simplify the problem/solution explanation above. Before the onset of a headache, one may feel tension building up in the shoulders, parts of the head, etc which we recognise as a symptom. To get rid of it, we typically pop a pill and the pain (symptom) goes away. However, if we do not fix the root cause of the headache (it could be due to life style, posture and so on), we will not be able to eradicate the problem. Applying the same idea, if you address the source of confusion i.e. unrecognised symbols, then confusion will not set in. If there is no confusion, it will not trigger disorientation. If a dyslexic is in an oriented state, you can at this point begin to teach a child to learn and you will notice that the child will register what is being taught. I always joke that there is only one thing consistent about dyslexics and that is, they are consistently inconsistent when it comes to learning. But once the obstacles causing the inconsistency are removed, then easeful learning can take place. The starting point is therefore not to teach a child how to learn (which many are doing by engaging tutors, sending them for enrichment classes and so forth), but to remove what’s preventing their ability to learn. To quote Ron, he said “if you remove the reason why a problem exists....the problem ceases to exist”. It is on this understanding that I put my daughter through the Davis programme and I have not looked back since. Just a quick recap, we’ve covered 2 of the 3 factors that explain how dyslexia develops, namely a dyslexic’s picture thinking style and perceptual talent.

The last factor that Ron talked about is a dyslexic’s special way of reacting to the feeling of confusion. He calls this disorientation. Ron said the symptoms of dyslexia that we see are actually symptoms of disorientation. What is disorientation? It is a state of mind where mental perceptions do not agree with the true facts and conditions in the environment. Most people experience disorientation at one point or another. One example is, you are sitting in a stationary vehicle and another vehicle next to you moves, creating a false perception that you are moving. For most of us, the disorientation we experience doesn't affect our day-to-day functioning. To a dyslexic, they disorient so frequently that it impacts their learning. So how does a dyslexic’s perceptual talent and disorientation help to explain the learning difficulties a dyslexic faces? This is how. In response to a symbol a dyslexic sees that confuses him, let’s say the letter ‘b’ (see illustration below), he will disorient in order to identify the letter he is looking at. He will start looking mentally at the letter from different angles. When it is a real object, like a chair, it doesn’t matter which angle he looks at. It will still look like a chair. But when it comes to 2-dimensional symbols, like a letter or word, looking at it from different locations gives a different picture each time. The letter ‘b’ can be a ‘d’, ‘p’ or ‘q’, depending on where the individual is looking from. So putting everything together, when a dyslexic sees a symbol which does not make sense to his picture thinking style, he gets confused and when that threshold for confusion is reached, it will trigger a disorientation and he will start looking mentally from different locations in order to figure out what he is looking at. When this happens, sensory perceptions become distorted and the brain receives an inaccurate input. This then manifests itself in mistakes. The resulting negative emotions that follow lead to low self-esteem and the child starts developing coping mechanisms such as concentrating harder, pushing through, dependency on others, giving excuses and so on. The whole vicious cycle repeats itself. Can you see how, if there is no solution to break that chain of causation, the child will continue to struggle and the learning gap gets wider and wider? In our next post, we will look at how to resolve the issues step by step. Don’t go away! In today’s post, we are going to look at the symptoms of dyslexia. Symptoms are tell tale signs that indicate possible issues one may be facing.

How do we pick up whether a child may be struggling with a learning issue? We look at the symptoms displayed by the child. We are all aware that humans have five basic senses: touch, smell, taste, sight and hearing. There are also two less known senses, which are vestibular and proprioception. The way our senses operate is that they work together to send information to the brain in order to help us make sense of our environment. When there is inaccurate input, it will lead to inaccurate output. Ron said that the symptoms of dyslexia are actually symptoms of disorientation (which I will touch on later) and affect four of our senses, namely vision, hearing, balance/coordination (which comes from the vestibular sense) and sense of time. Below is a list of some of the more common symptoms affecting each of our four senses, but they are by no means exhaustive. Vision: - shapes and sequences of letters or numbers appear changed or reversed - spelling is incorrect or inconsistent - words or lines are skipped when reading or writing - punctuation marks or capital letters are omitted, ignored or not seen - words and letters are omitted, altered or substituted while reading or writing Hearing: - some speech sounds are difficult to make - diagraphs such as ch, th and sh are mispronounced - “false” sounds are perceived - what is said does not appear to be listened to or heard Balance/Movement: - dizziness or nausea while reading - poor sense of direction - inability to sit still - difficulty with handwriting - problem with balance and coordination Time: - hyperactivity (overactive) - hypoactivity (underactive) - difficulty learning math concepts - difficulty being on time or telling time - excessive day dreaming - frequent loss of train of thought - trouble sequencing (putting things in the correct order) How many symptoms on the list did you tick off that correspond with what you see in your child? What should you do next? Who should you approach for help? What is the difference between screening and assessment? Stay tuned to our next post! I first came across this statement 10 years ago when I laid my hands on the book, The Gift of Dyslexia by Ronald D. Davis, an American who was diagnosed with autism and dyslexia. That caught my attention.

Ron went on to elaborate that “dyslexia is a product of thought, talent and a special way of reacting to the feeling of confusion.” I will be breaking down Ron’s explanations into bite-sized posts in the coming days. I hope the information will give you another perspective of looking at dyslexia and possibly direct your next step. What is dyslexia? It is a language based, specific learning difficulty that impacts reading, spelling, comprehension, handwriting (dysgraphia), math (dyscalculia) as well as balance and coordination (dyspraxia). Dyslexia has to do with the way the brain is wired. While most of us use our left brain to process languages, dyslexics use their right brain or the creative brain, which is responsible for daydreaming and imagination. Dyslexia is not due to a lack of intelligence. For a dyslexia diagnosis, a person’s IQ needs to be at least in the normal range. That said, a below average IQ may not necessarily indicate the absence of dyslexia. Ron was initially tested to have low IQ and was labelled as “uneducatably mentally retarded” at the age of 12, but was later discovered to have an extremely high IQ of 137. In other words, a person cannot be dumb and dyslexic. For a child with dyslexia, he/she is often misunderstood as being lazy, not interested in learning, not trying hard enough and/or gets distracted easily. As parents, I am sure such thoughts crossed our minds. In the next post, we will be looking at the symptoms of dyslexia. These symptoms are often red flags that alert parents to their child’s struggles. Stay tuned! The majority of children could tackle a question like this with ease. However, to those children with dyslexia, they may stumble over such question. Why is that so?

Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. When they encounter certain symbols (and all words are symbols), they get confused by those whose meaning they cannot picture. These are often high frequency words that we use a lot of in the English language, such as ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘by’, ‘to’, etc. When they cannot begin to think with that word in picture, they do not know how to make sense of a sentence. So in the example question above, a dyslexic may be confused by the word ‘from’. The child may be able to recognise and pronounce the word ‘from’ when he sees it, but he does not know the meaning and so he does not know what he needs to do to begin to solve the question. After much drilling and repetition to no avail to help the child understand the question, the child is then told by a well-meaning parent or tutor that whenever he sees such questions, he just needs to take the bigger number and minus the smaller number. By doing so, the child is taught rote learning, rather than have real understanding or true mastery of the subject. If we could acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style, we can help the child master the meaning of ‘from’ and let him create a picture of what it means. According to the American Heritage Children’s Dictionary, ‘from’ means beginning at, starting with. Once the child understands the meaning, he can now picture what the question is asking him to do. Subtract 79 from 139 means that he has to begin at, start with (ie from) 139, and then minus or take away 79, in order to derive at the answer. Visually, he would be able to put 139 down on paper, followed by the minus sign and 79 below 139 and then do his workings to get to the answer. By extension, a dyslexic child very often can’t do problem sums not because he does not have the skill to do arithmetic, but because he does not understand what the question is asking of him in the first place, as he can’t think with some of the words that are in the question. More than 30 years ago, Ron Davis had it figured out that dyslexia is not something complex but rather, it is a compound of simple factors that can be resolved step by step.

He explained that dyslexia is actually a product of a dyslexic’s picture thinking style, their ability to see things 3-dimensionally and their unique way of reacting to the feeling of confusion when they see symbols that they do not recognise (and all words are symbols). Because of these 3 factors at work, dyslexics encounter the difficulties we see in them when learning to read, write and spell. This video illustrates what picture thinking vs word thinking is like and why dyslexics do not seem to recognise the same word which they learnt just seconds ago and as a result, produced mistakes in their reading, writing and spelling. It’s only by understanding this then can we tackle the root of the problem. Ron said that once we remove the reason why a problem exists, the problem ceases to exist. How simple and logical is that? Once I understood Ron’s explanation, I knew instinctively that he had the right solution and I did not hesitate to put my daughter through the Davis intervention programme.

Q: Can you explain with an example, how a dyslexic gets confused when reading, and how that leads to disorientation when the threshold for confusion is reached, and subsequently mistakes are made in the process? A: Let me unpack this for you by using Ron Davis’ step-by-step breakdown of what happens when a 10-year old dyslexic reads the sentence, “The brown horse jumped over the stone fence and ran through the pasture”. The first word “the” caused the mental imagery to go blank, because there was no picture for it. A blank picture is the essence of confusion. Using concentration, however, the child pushes past the blank picture and says “the” and forces himself to skip to the next word. The word “brown” produces the mental image of a colour, but it has no defined shape. Continuing to concentrate, he says the word “brown”. The word “horse” transforms the brown picture into a horse of that colour. Concentration continues and “horse” is said. The word “jumped” causes the front of the brown horse to rise into the air. He continues concentrating as he says “jumped”. The word “over” causes the back of the horse to rise. Still concentrating, he says “over”. The next word, another “the”, causes the picture to go blank again. Confusion for the dyslexic has increased, but the threshold for confusion has not been reached. He must now double his concentration so he can push on to the next word. In doing so, he may or may not omit saying “the”. The word “stone” produces a picture of a rock. With concentration doubled, he says “stone”. The next word, “fence”, turns the rock into a rock fence. Still with doubled concentration, he says “stone”. The next word, “and”, blanks out the picture again. This time, the threshold for confusion is reached. So the child becomes disoriented. The child is stopped again, more confused, doubly concentrating, and more disoriented. The only way he can continue is to increase his concentration effort. But now because he is so disoriented, the dyslexic symptoms will appear. It is very likely that he will omit saying the word “and”, or just as likely that he will substitute “a”, “an”, or “the” instead. At this point, he is no longer getting an accurate perception of the words on the page. He is now expanding a tremendous amount of effort and energy on concentrating, just to continue. The next word, “ran”, because he is now disoriented, is altered into the word “runs”. He sees an image of himself running, entirely unrelated to the picture of the hovering horse. Then he says “runs”. The word “through” is altered into “throws”. He sees himself throwing a ball and says “throws”. The next word, “the”, blanks out the picture again, even more confused, and still disoriented. His only recourse is to quadruple his concentration. In doing so, he omits saying “the”. By now, his disorientation has created a feeling like dizziness. He is feeling sick to his stomach, and the words and letters are swimming around on the page. For the last word “pasture”, he must track down each letter, one at a time, so he can sound out the word. Once he does, he sees a picture of a grassy place. Even though he is disoriented, because of the extra effort and energy he puts forth in catching and sounding out each letter, he says it right, “pasture”. Having competed the sentence, he closes the book and pushes it away. That’s enough of that! When asked what he just read, he is likely to answer with something like “a place where grass grows”. He has a picture of a horse in the air, a stone fence, himself playing ball and a grassy place, but cannot relate the separate elements in the sentence to form a mental image of the scene described. To everyone who saw or heard him read the sentence or heard his answer to what it was about, it’s obvious that he didn’t understand any of what he just read. As for him, he doesn’t care that he didn’t understand it. He’s just thankful that he survived the ordeal of reading out loud. Do you see some similarities between what was described above and what you see in your child when he/she attempts to read?  The mistakes we see a dyslexic make when reading, such as omissions, substitutions, insertions and reversals, are as a result of disorientation. Disorientation causes perceptual distortions in our various senses: vision, hearing, balance/movement and sense of time. Just like the idea depicted in the picture, dyslexics need a way to ‘refresh’ their sensory perceptions so that they can turn off the disorientation, and have accurate perception. |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed