Did you know that dyslexics can think and visualise in 3D images? This perceptual talent is also one of the contributing factors to their learning difficulties. This video provides a good explanation on how this perceptual talent works and how it causes mistakes in a learning situation when it is engaged.

0 Comments

How many of you can read the text easily without having to pause and figure out the sequence of letters in order to make out a recognisable word? One of the symptoms of dyslexia we look for is to observe whether the child is persistently misreading words (such as house for horse, was for saw, etc). Our minds typically scan the whole word (and not every letter of the word) when reading. When in an oriented state, we do not make reading mistakes. However, a dyslexic is easily confused whenever they encounter letters, punctuation marks and high frequency words. Those symbols trigger disorientation which in turn leads to perceptual distortion which results in mistakes. Having accurate perception is important for reading accuracy. A dyslexic’s place of orientation when perceiving a text is often not at the optimal place. Putting oneself in an oriented state is the key to turning off the disorientation and gaining accurate perception. Francis is a Physical Education teacher at Outram Secondary School. He is also the recipient of the President’s Award for Teachers 2020. Francis was instrumental in transforming the school’s water polo team, leading them to the finals in the interschool league in 2011, after their last one 19 years ago.

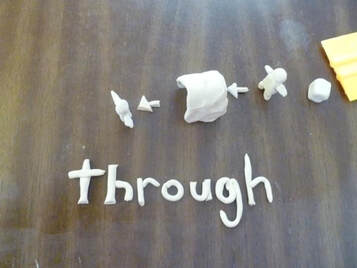

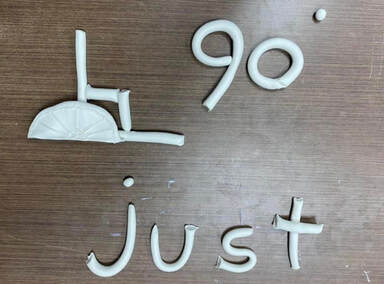

Trained as a Teacher for Special Needs at NIE, Francis suspected he could be dyslexic and was formally diagnosed six months ago. With the diagnosis, things are coming together for him. He now understands his strengths better and what works for those with special education needs. Working with his fellow teachers, the school implemented study groups where students help each other to learn. This set up has yielded impressive results as the students grew in self-confidence which translated to academic achievements. How did you first find out that you are dyslexic? I was trained as a Teacher for Special Needs. As a lead teacher, I mentor teachers in the school in special education needs. As I delve deeper into this area, I began suspecting I could be dyslexic. I remember reading a book on the strengths of neurodivergent children and saw some of the traits in myself. Six months ago, I went through an assessment at the Dyslexia Association of Singapore which confirmed my suspicion. I wanted a diagnosis so that from a dyslexic's perspective, I can share why some of the teaching pedagogies such as collaborative learning actually works. What was life like as a student prior to your dyslexia diagnosis? I knew I was a slower learner compared to my peers. I started picking up reading only in secondary school and languages were not my strength. My teachers used to call me lazy and my handwriting was untidy. But I did notice that I learn faster than others in certain areas. For example, I was quick at grasping concepts and can see 3D images easily. My secondary school had an after-school study programme where students were divided into smaller groups to help one another learn. That was very helpful for me. I was always stressed about keeping up with my peers in class. Having a group of friends helping each other made the learning environment less pressurising. As I grew older, I developed lower self-esteem. I started reading self-help books as I wanted to build a positive growth mindset. Each time I tried something and failed, I told myself it was another chance for me to try again. As I build up my confidence, I started getting better at what I do, such as playing sports and my studies in the university. What inspired you to become a teacher? I believe that if more teachers form study groups and help the students build self-confidence, more of them would enjoy studying and do better in life. That influenced my decision to be a teacher. As a teacher, I now understand why many students are inattentive in class and I tried different methods to engage them. For example, I formed study groups in my form class and in the water polo CCA I am in charge of. I also encourage the use of peer coaching and collaborative learning with other teachers. This has helped many teachers engage with more students. In my school, more teachers are now using collaborative learning as the main teaching pedagogy. Students are given a problem to solve at the start of the lesson. Through inquiry-based learning, students with special education needs learn better. Tapping on their strengths and helping each other increase their self-efficacy. I am sure you came across many students who struggle with different learning challenges. What words of encouragement do you have for them? As a teacher of 15 years, I see many strengths in students with special education needs. While most of us focus on their failures or weaknesses, they should be recognised for their strengths. Very often, a person with ADHD finds it difficult to focus on boring lectures. They need something that challenges them and I have seen many ADHD students who are good at solving challenging science problems. The slightest of sound could be magnified and bother a person with ASD, but this same trait allows him to spot the small details. Although dyslexics take a longer time to read, we ended up having better understanding and could grasp the concepts. Those students that I know of who are dyslexic had a knack for linking the different concepts together. They definitely make very good peer teachers. Does having a diagnosis make any difference to the way you look at your learning difficulties and is there any positive outcome arising from the diagnosis? As I was diagnosed only six months ago, there hasn’t been many changes. My personal transformation has been a growth mindset and self-belief. I think people who are neurodiverse need to stay positive. It is easy to see ourselves as being inferior to others and give up on ourselves. After my diagnosis, I have a better understanding of the traits I possess. I can see my ability in connecting the different teaching pedagogies and applying them effectively in the classroom. Some parents are still reluctant to send their children for diagnosis for fear of labelling them and putting them at a disadvantage. Now that you are an adult and looking back at your younger days, what are your thoughts on this? Since my diagnosis, I have been able to explain to parents the benefits of being neurodiverse. The world needs people who are innovative, able to see the big picture and are self-directed learners. These are traits commonly present in neurodiverse people. When parents heard this, they are more incline to send their children for assessments. I also share about my own learning difficulties and my strengths with my students. After hearing my experiences, more students are starting to realise their strengths and this helps to boost their confidence. How do you perceive dyslexia now that you are an adult, and do you see dyslexia more as a learning difference rather than a limitation? It is definitely a learning difference. Yes, I do struggle in some areas, but with the help of technology, things are much easier for me compared to before. I have also overcome my limitations by using different strategies such as asking my colleagues for help.  The learning process for dyslexics requires active involvement. Quoting Ron Davis, he said “the creative process and the learning process, if not the same thing, are so closely associated that we will never be able to separate them.” Creativity is therefore an essential part of the learning process. If we create something in the form of memorisation, what we have is something memorised. If we create something in the form of understanding, what we have is understanding. Ron said that if you create something, you can own it. If you can own it, you can experience it. If you can experience it, you can master it, and if you can master it, it becomes part of your thinking process. Try observing your child when he/she is reading. Make a note of the words your child substituted, skipped, inserted, misread or hesitated. Excluding those words your child is unfamiliar with, you will notice that most of the words where mistakes are made are high frequency words such as ‘the’, ‘of’, ‘at’, etc. Being picture thinkers, these words often produce a blank picture for the child whenever he/she comes across it. The child may know how to spell and/or pronounce the word, but because there is no picture representing what the word means, it becomes a source of confusion for him/her. To resolve the confusion, the child needs to ‘create’ for himself/herself the meaning of the words he/she has difficulty using, spelling, reading, writing or understanding. In the Davis approach, we do this through an exercise called Symbol Mastery (see pic). Using plasticine clay as a medium, the child gets to engage his/her creativity in the course of learning and the outcome is that he/she receives a learning experience that is more impactful and permanent compared to memorisation (which many of our kids do) or writing 10 or 20 times in order to learn each spelling word, etc. To draw a parallel of what I mean, no matter how often we watch someone riding a bicycle and read about what needs to be done, the understanding of it won’t keep us from falling over the first time we get on the bike. Mastering riding the bike requires that we get on the bike and experiencing it for ourselves personally. We have to create that experience in the real world in order to master it. Therefore, when dyslexics create the meaning of the word (that causes confusion) in clay, and then add what the word looks like and sounds like, they are doing what is similar to getting on the bike and experiencing the learning for themselves. That is what mastery is and when a word is mastered, it no longer causes confusion for the child and actual learning can then take place. Following my previous post which talked about a dyslexic’s perceptual talent, it is equally important to understand a dyslexic’s thinking style.

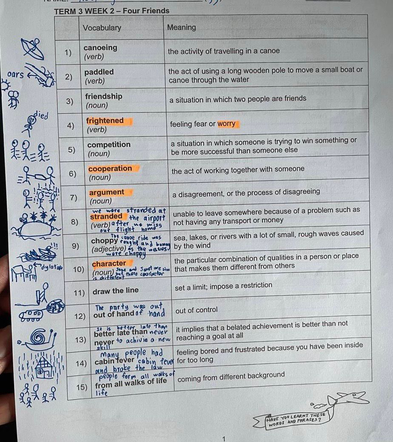

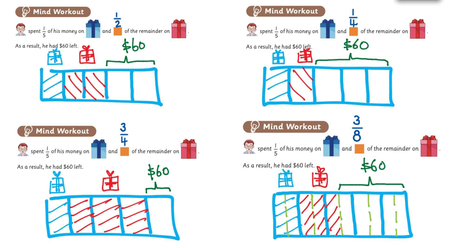

We typically think in 2 ways: word thinking and picture thinking. Word thinking is simply thinking with the sounds of words in your mind. It is a monologue that goes on in your head. I often find myself engaging in word thinking for example, when I rehearse a presentation I’m going to give, or sorting out a problem in my head, etc. Picture thinking, a preference for most dyslexics, is about mental imagery. It is thinking with any of the senses (sound, smell, taste, feeling, visual) in our imagination. A dyslexic chef I once interviewed described how he can mentally picture the taste of a dish he is creating before actually testing it out in reality. When you give direction to someone, we most likely see pictures of where the person needs to go and the pictures then give you the words to say to the person. Dyslexics find it easier to retain information when they see mental images as opposed to words. Try this experiment. Ask your child to draw a couple of random pictures (simple ones and suggest drawing 6 pictures upwards) and write down similar number of random words not related to the pictures. Then get your child to point to each of the drawing and name it, then point to each of the word and say it. Next, ask your child to close his/her eyes and see whether it’s easier for him/her to recall the drawings or the words. This exercise should give you a clue as to whether your child is more of a word or picture thinker. To prove my point further, the picture above is a spelling list shared with me by the parent of a dyslexic boy (who had undergone the Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme). See how he doodled next to the words. By drawing a representation or idea of what the word means, it helped him to attach a visual image to the words. Unlike before where he used to just memorise his spelling words (and even then, not all the words would stick for him), his retention of words has gone up once he understands and knows how to work with his strength (creating mental pictures) rather than weakness (memorising). The problem sums featured above are typical of our math curriculum.

Very often, our dyslexic children struggle to comprehend the questions. There are potential ‘minefields’ in these questions that could set off a chain of confusion for them. You see them re-reading the questions. Frowns start to form, fingers start tapping on the table, they start fidgeting and soon, they throw their hands in the air and exclaim that they do not know how to do the questions. Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. When they encounter certain symbols (be it words or numerals), they get confused by those whose meaning they cannot picture. When they cannot begin to think with that word or concept (such as addition, multiplication, fraction, place value, etc) in picture, they do not know how to make sense of a sentence. In the case of these problem sums, a dyslexic may be confused by the words ‘of’, ‘on’, ‘and’, ‘remainder’ and even concepts of what ‘1/5’, ‘1/2’, ‘1/4’, ‘3/4’, ‘3/8’ mean. Because the child does not know the meaning, he does not know what he needs to do to begin to solve the questions. The first step to help the child is to acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style. The child needs to master not only the meaning of those high frequency words used in math by having a picture or image of what they mean but also be able to picture what the different fractions look like. Very often, a dyslexic child’s struggle with problem sums is not because he does not have the skill to do arithmetic, but because he does not understand what the question is asking of him in the first place, as he cannot think with some of the words or concepts that are in the questions. I recently facilitated a 5 days Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme with an adult dyslexic. Diagnosed in primary school, she received short term intervention then. She is a good reader and spelling is not an issue, but struggles to comprehend what she is reading.

During the programme week, she realised what impacted her comprehension. While she reads fluently, her pace of reading was quite fast and she was not even aware whenever she made reading mistakes. It also dawned on her that she did not have a good understanding of some of the punctuation marks used. Punctuation gives meaning to what we’re reading. The lack of certainty on how each punctuation mark is used and what to do when we come across them (whether to stop, pause, continue reading) added to her confusion. Another thing that struck her was the realisation that she did not really know the meaning of some of the high frequency words (such as by, when, who, which) she encountered in reading. She identified the word “just” as being the most confusing for her and did symbol mastery (see picture below) in order to have clarity of the meaning and that resolved her confusion. “Just” means exactly, precisely. Can you see the meaning in her clay model? The protractor was used to give an exact, precise measurement of the right angle. Once she masters the punctuation marks, resolves any words that caused confusion, slows down when reading and converts what she reads into pictures, she begins to have better comprehension of and retains what she is reading. Photo credit: Vernon Leow

Google Willin Low and the search engine throws up a list of write-ups about him. A lawyer-turned-chef/restaurateur, Willin left his cushy career as a lawyer after eight years to pursue his dream as a chef. While most people know Willin as the chef/restaurateur behind Wild Rocket, his flagship restaurant that has not only hosted our Prime Minister, celebrities and dignitaries, he was also named one of three chefs to change the Singapore culinary scene by The New York Times. He is the originator of “Mod Sin” or Modern Singaporean cuisine, a term coined by Willin when he was studying in the UK and describes his style of cuisine. I understand you have not been officially diagnosed with dyslexia. It was your brother, a doctor, who suspected you could be dyslexic. Could you tell us what led to that suspicion? I was getting the names of people wrong again. I usually only remember the first letter of the names. For example, if someone is called Andrew, I will always say that person’s name starts with the letter A. And on one such occasion, my brother, a doctor, said “I think you are dyslexic!” And proceeded to ask me a few other questions before concluding that I am. And it was at this point that everything suddenly made sense to me. As a student, what struggles did you face? There were three subjects that I just could not follow as a student: 1. Chemistry in Upper Secondary, especially the periodic table. It was just a nightmare and my Chemistry teacher kept picking on me and taunting me. She made life hell for me. I guess you can say we did not have much chemistry (smiles). I learnt that in life, not everyone will like you or make life a breeze for you. 2. Economics in JC. I just could not follow any of the concepts. It was as though everything was taught in a foreign language. Later on in life as I ran my own restaurants, I understand all the economic concepts so easily and wondered why I never did well in Economics. 3. Accounting. I did a module in accounts in university and it was the worst thing ever. All the numbers and tables just looked completely alien. I think my professor passed me out of pity (laughs). How did you manage to do so well academically and ended up reading law in university? Given the heavy reading involved, how did you cope? Reading isn’t a problem for me as much as writing is. Chinese characters and numbers are much more difficult for me. I recall being in tears in kindergarten as I kept writing the mirror image of the Chinese character for knife (刀). Spelling is also an issue. I tend to spell words as I hear them. My parents blamed my carelessness. Since I didn’t know I was dyslexic, I just assumed everyone else had the same problems as me. I kept calm and carried on. What got you started on your journey to becoming a chef? Was cooking something you have always been passionate about? How was that passion cultivated? I love eating and I am a very fussy eater. When I was a student in the UK, the food at the halls of residence was dismal and out of necessity, I started cooking and soon discovered another passion, that I love making people happy through food. How was your flagship restaurant, Wild Rocket conceptualised and what was the creative process that went into the creation of the dishes? I read that you love taking apart what is a traditional dish, rehash them and change it into something different while retaining the spirit of the dish. Was it something very spontaneous and instinctive to you? Again, it started when I was cooking in the UK. I missed Singapore food but could never find all the ingredients I needed so I had to improvise with whatever I could get my hands on. The result never looked like Singapore food but always tasted like home. I call this cuisine Mod Sin and it stuck. Yes, creating dishes come quite instinctively and most times, I taste the food in my head first before I cook it and taste it in my mouth. And all my food creations start with drawings. Dyslexics are known to be strategic, big picture thinkers. How do you think that might have helped you in your role as a chef/restaurateur? Ah, another piece of the puzzle (laughs). I did not realise it was linked to my dyslexia. Yes, I am always looking at the big picture of what I want to achieve, whether it’s the Mod Sin cuisine or more specifically my restaurants, and it serves as a guiding principle for the steps I take thereafter. As an adult now, do you struggle with things that dyslexics tend to be weaker at, such as poor working memory, slow processing speed and organisation of thoughts. Can you give some examples? In order for me to understand anything, I need to organise it in a way that I can understand. I draw mind maps to see the overall big picture in order to understand the small details. I also cannot concentrate on just doing one thing. I need to do many things at the same time. I suspect I may have ADHD. I manage by doing three things at one time so I can concentrate. For example, I will study Japanese, exercise and watch tv at the same time. I will think in my head the correct telephone or account number but when I type it out it’s wrong. This happens regularly and I manage by checking and rechecking when I do online banking. Verbal directions are most stressful. I cannot follow after the second step. To manage, I take videos of demonstrations on how to operate electronic gadgets. Lastly, you were part of a movement called Life Beyond Grades, where its aim is to remind parents and children alike that grades do not define us. How did your parents encourage you as a child/student? On the eve of my Secondary 2 geography exams, I was panicking because I was ill prepared. Dad told me it’s ok to fail, but important to learn from the failure. He said failing isn’t the end of the world so don’t worry, keep calm and carry on. Today, I want to touch on intervention programmes. This is one area that parents find mind boggling.

The key to helping a child struggling with dyslexia is early identification and intervention. Very often, I see the identification process being delayed because of lack of knowledge or parents did not pick up the red flags. I went with my gut feel even when educators and doctors I consulted dismissed my concerns. These are people we deem as professionals and I fully respect them. But I have learnt that they may not necessarily be the best person to dispense advice. With persistency, I eventually spoke to a psychologist friend who pointed me in the direction of dyslexia and as a result, my daughter was diagnosed early and received intervention at 6 years old. As far as intervention goes, different theories create different approaches. We should get it by now that dyslexics have an alternative way of thinking and learning. If we continue to look at dyslexia as a deficit instead of working with a dyslexic’s strengths, we are adding yet another obstacle to the child’s remediation journey. To give you an example, because people still think the only way to decode a word is through phonics and if the child finds it difficult to process the sounds of letters or blending, they see it as a deficit and therefore, with all good intention, try to equip the child through drilling and repetitions. Many intervention programmes target the symptoms and not the root cause. You may take the position that if a particular programme helps with a certain issue, such as the ability to recall and retain a spelling word learnt, why not? To me, the bigger question is, how about the child’s challenges in other areas such as decoding ability, reading fluency or comprehension? All these are necessary components of learning. Without a holistic approach, the child may seem to have made some progress in a certain area, but making progress is not the same as closing the gap. If a child is making progress, he or she may still be falling behind. Therefore when evaluating any intervention programmes, keep in mind what we have learnt about how dyslexia develops. Find out if the programme works with a dyslexic’s strengths or is the focus still on what the child can’t do? How does the programme help the child resolve his confusion with common sight words? What is the approach to reading fluency and comprehension? Many parents have the misconception that their child is dealing with some complex learning difficulties that will need long term intervention and that they will not perform as well as their peers. This need not be the case. Dyslexia is a learning difference, not a limitation. It is a gift, not a disability. Approach correctly, your child can be remediated successfully. Of course, the child has to have the motivation to want to correct the problem and is able and willing to take responsibility for doing so. To understand dyslexia is to know how it develops, not from the etiology angle, but how it happens functionally. Ron gave us an insight when he identified the 3 factors at work which led to the learning issue.

I have done up the flow chart above which hopefully gives you a clearer picture. It all starts with words/symbols that a dyslexic sees that confuses him. When he is confused enough, he will disorient and start to look from different locations mentally. The disorientation causes perceptual distortion which in turn produces the mistakes which we recognise as dyslexic symptoms. Now that we realise the true nature of a problem, we need a solution, and Ron has developed a 2-pronged approach to correct dyslexia. First off, since disorientation causes perceptual distortion of our senses which then manifests in mistakes, dyslexics need a way to ‘turn off’ their disorientation in order to have accurate perception. To this end, Ron has figured a way for dyslexics to mentally ‘switch off’ that disorientation when it happens, so that the individual will have a stable point of reference when looking at 2-dimensional text. But having accurate perception is not enough. We need to resolve the root cause of confusion. Given that the source of confusion comes from trigger words (which are mostly common sight words), a dyslexic needs to master these words with all its 3 parts, in order for them not to cause any problem for the individual. The 3 parts are (i) what the word means (which will be in the form of a picture to cater to the dyslexic’s picture thinking style), (ii) what it looks like (which is how you spell it) and (iii) what it sounds like (which is how you pronounce the word). A dyslexic may know what a word looks like and sounds like, but if he is missing the picture of what it means or represents, it will produce a blank picture and that adds to the confusion. I like to use the analogy of a headache to simplify the problem/solution explanation above. Before the onset of a headache, one may feel tension building up in the shoulders, parts of the head, etc which we recognise as a symptom. To get rid of it, we typically pop a pill and the pain (symptom) goes away. However, if we do not fix the root cause of the headache (it could be due to life style, posture and so on), we will not be able to eradicate the problem. Applying the same idea, if you address the source of confusion i.e. unrecognised symbols, then confusion will not set in. If there is no confusion, it will not trigger disorientation. If a dyslexic is in an oriented state, you can at this point begin to teach a child to learn and you will notice that the child will register what is being taught. I always joke that there is only one thing consistent about dyslexics and that is, they are consistently inconsistent when it comes to learning. But once the obstacles causing the inconsistency are removed, then easeful learning can take place. The starting point is therefore not to teach a child how to learn (which many are doing by engaging tutors, sending them for enrichment classes and so forth), but to remove what’s preventing their ability to learn. To quote Ron, he said “if you remove the reason why a problem exists....the problem ceases to exist”. It is on this understanding that I put my daughter through the Davis programme and I have not looked back since. |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed