Did you know that dyslexics can think and visualise in 3D images? This perceptual talent is also one of the contributing factors to their learning difficulties. This video provides a good explanation on how this perceptual talent works and how it causes mistakes in a learning situation when it is engaged.

0 Comments

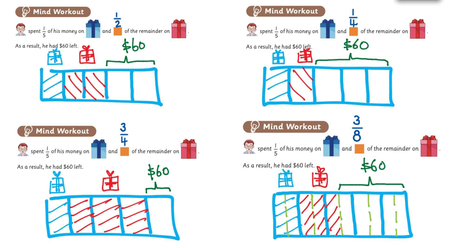

The problem sums featured above are typical of our math curriculum.

Very often, our dyslexic children struggle to comprehend the questions. There are potential ‘minefields’ in these questions that could set off a chain of confusion for them. You see them re-reading the questions. Frowns start to form, fingers start tapping on the table, they start fidgeting and soon, they throw their hands in the air and exclaim that they do not know how to do the questions. Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. When they encounter certain symbols (be it words or numerals), they get confused by those whose meaning they cannot picture. When they cannot begin to think with that word or concept (such as addition, multiplication, fraction, place value, etc) in picture, they do not know how to make sense of a sentence. In the case of these problem sums, a dyslexic may be confused by the words ‘of’, ‘on’, ‘and’, ‘remainder’ and even concepts of what ‘1/5’, ‘1/2’, ‘1/4’, ‘3/4’, ‘3/8’ mean. Because the child does not know the meaning, he does not know what he needs to do to begin to solve the questions. The first step to help the child is to acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style. The child needs to master not only the meaning of those high frequency words used in math by having a picture or image of what they mean but also be able to picture what the different fractions look like. Very often, a dyslexic child’s struggle with problem sums is not because he does not have the skill to do arithmetic, but because he does not understand what the question is asking of him in the first place, as he cannot think with some of the words or concepts that are in the questions. I recently facilitated a 5 days Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme with an adult dyslexic. Diagnosed in primary school, she received short term intervention then. She is a good reader and spelling is not an issue, but struggles to comprehend what she is reading.

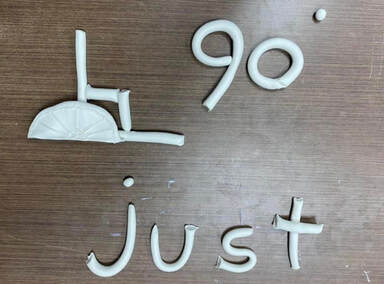

During the programme week, she realised what impacted her comprehension. While she reads fluently, her pace of reading was quite fast and she was not even aware whenever she made reading mistakes. It also dawned on her that she did not have a good understanding of some of the punctuation marks used. Punctuation gives meaning to what we’re reading. The lack of certainty on how each punctuation mark is used and what to do when we come across them (whether to stop, pause, continue reading) added to her confusion. Another thing that struck her was the realisation that she did not really know the meaning of some of the high frequency words (such as by, when, who, which) she encountered in reading. She identified the word “just” as being the most confusing for her and did symbol mastery (see picture below) in order to have clarity of the meaning and that resolved her confusion. “Just” means exactly, precisely. Can you see the meaning in her clay model? The protractor was used to give an exact, precise measurement of the right angle. Once she masters the punctuation marks, resolves any words that caused confusion, slows down when reading and converts what she reads into pictures, she begins to have better comprehension of and retains what she is reading. Today, I want to touch on intervention programmes. This is one area that parents find mind boggling.

The key to helping a child struggling with dyslexia is early identification and intervention. Very often, I see the identification process being delayed because of lack of knowledge or parents did not pick up the red flags. I went with my gut feel even when educators and doctors I consulted dismissed my concerns. These are people we deem as professionals and I fully respect them. But I have learnt that they may not necessarily be the best person to dispense advice. With persistency, I eventually spoke to a psychologist friend who pointed me in the direction of dyslexia and as a result, my daughter was diagnosed early and received intervention at 6 years old. As far as intervention goes, different theories create different approaches. We should get it by now that dyslexics have an alternative way of thinking and learning. If we continue to look at dyslexia as a deficit instead of working with a dyslexic’s strengths, we are adding yet another obstacle to the child’s remediation journey. To give you an example, because people still think the only way to decode a word is through phonics and if the child finds it difficult to process the sounds of letters or blending, they see it as a deficit and therefore, with all good intention, try to equip the child through drilling and repetitions. Many intervention programmes target the symptoms and not the root cause. You may take the position that if a particular programme helps with a certain issue, such as the ability to recall and retain a spelling word learnt, why not? To me, the bigger question is, how about the child’s challenges in other areas such as decoding ability, reading fluency or comprehension? All these are necessary components of learning. Without a holistic approach, the child may seem to have made some progress in a certain area, but making progress is not the same as closing the gap. If a child is making progress, he or she may still be falling behind. Therefore when evaluating any intervention programmes, keep in mind what we have learnt about how dyslexia develops. Find out if the programme works with a dyslexic’s strengths or is the focus still on what the child can’t do? How does the programme help the child resolve his confusion with common sight words? What is the approach to reading fluency and comprehension? Many parents have the misconception that their child is dealing with some complex learning difficulties that will need long term intervention and that they will not perform as well as their peers. This need not be the case. Dyslexia is a learning difference, not a limitation. It is a gift, not a disability. Approach correctly, your child can be remediated successfully. Of course, the child has to have the motivation to want to correct the problem and is able and willing to take responsibility for doing so. To understand dyslexia is to know how it develops, not from the etiology angle, but how it happens functionally. Ron gave us an insight when he identified the 3 factors at work which led to the learning issue.

I have done up the flow chart above which hopefully gives you a clearer picture. It all starts with words/symbols that a dyslexic sees that confuses him. When he is confused enough, he will disorient and start to look from different locations mentally. The disorientation causes perceptual distortion which in turn produces the mistakes which we recognise as dyslexic symptoms. Now that we realise the true nature of a problem, we need a solution, and Ron has developed a 2-pronged approach to correct dyslexia. First off, since disorientation causes perceptual distortion of our senses which then manifests in mistakes, dyslexics need a way to ‘turn off’ their disorientation in order to have accurate perception. To this end, Ron has figured a way for dyslexics to mentally ‘switch off’ that disorientation when it happens, so that the individual will have a stable point of reference when looking at 2-dimensional text. But having accurate perception is not enough. We need to resolve the root cause of confusion. Given that the source of confusion comes from trigger words (which are mostly common sight words), a dyslexic needs to master these words with all its 3 parts, in order for them not to cause any problem for the individual. The 3 parts are (i) what the word means (which will be in the form of a picture to cater to the dyslexic’s picture thinking style), (ii) what it looks like (which is how you spell it) and (iii) what it sounds like (which is how you pronounce the word). A dyslexic may know what a word looks like and sounds like, but if he is missing the picture of what it means or represents, it will produce a blank picture and that adds to the confusion. I like to use the analogy of a headache to simplify the problem/solution explanation above. Before the onset of a headache, one may feel tension building up in the shoulders, parts of the head, etc which we recognise as a symptom. To get rid of it, we typically pop a pill and the pain (symptom) goes away. However, if we do not fix the root cause of the headache (it could be due to life style, posture and so on), we will not be able to eradicate the problem. Applying the same idea, if you address the source of confusion i.e. unrecognised symbols, then confusion will not set in. If there is no confusion, it will not trigger disorientation. If a dyslexic is in an oriented state, you can at this point begin to teach a child to learn and you will notice that the child will register what is being taught. I always joke that there is only one thing consistent about dyslexics and that is, they are consistently inconsistent when it comes to learning. But once the obstacles causing the inconsistency are removed, then easeful learning can take place. The starting point is therefore not to teach a child how to learn (which many are doing by engaging tutors, sending them for enrichment classes and so forth), but to remove what’s preventing their ability to learn. To quote Ron, he said “if you remove the reason why a problem exists....the problem ceases to exist”. It is on this understanding that I put my daughter through the Davis programme and I have not looked back since. Just a quick recap, we’ve covered 2 of the 3 factors that explain how dyslexia develops, namely a dyslexic’s picture thinking style and perceptual talent.

The last factor that Ron talked about is a dyslexic’s special way of reacting to the feeling of confusion. He calls this disorientation. Ron said the symptoms of dyslexia that we see are actually symptoms of disorientation. What is disorientation? It is a state of mind where mental perceptions do not agree with the true facts and conditions in the environment. Most people experience disorientation at one point or another. One example is, you are sitting in a stationary vehicle and another vehicle next to you moves, creating a false perception that you are moving. For most of us, the disorientation we experience doesn't affect our day-to-day functioning. To a dyslexic, they disorient so frequently that it impacts their learning. So how does a dyslexic’s perceptual talent and disorientation help to explain the learning difficulties a dyslexic faces? This is how. In response to a symbol a dyslexic sees that confuses him, let’s say the letter ‘b’ (see illustration below), he will disorient in order to identify the letter he is looking at. He will start looking mentally at the letter from different angles. When it is a real object, like a chair, it doesn’t matter which angle he looks at. It will still look like a chair. But when it comes to 2-dimensional symbols, like a letter or word, looking at it from different locations gives a different picture each time. The letter ‘b’ can be a ‘d’, ‘p’ or ‘q’, depending on where the individual is looking from. So putting everything together, when a dyslexic sees a symbol which does not make sense to his picture thinking style, he gets confused and when that threshold for confusion is reached, it will trigger a disorientation and he will start looking mentally from different locations in order to figure out what he is looking at. When this happens, sensory perceptions become distorted and the brain receives an inaccurate input. This then manifests itself in mistakes. The resulting negative emotions that follow lead to low self-esteem and the child starts developing coping mechanisms such as concentrating harder, pushing through, dependency on others, giving excuses and so on. The whole vicious cycle repeats itself. Can you see how, if there is no solution to break that chain of causation, the child will continue to struggle and the learning gap gets wider and wider? In our next post, we will look at how to resolve the issues step by step. Don’t go away! In our previous post, we looked at a dyslexic’s picture thinking style and how this can cause confusion for them whenever they encounter words whose meaning they cannot picture. 75% of a page consists of such trigger words and it’s no wonder when they try to read, they would make mistakes.

Today, we’ll look at a dyslexic’s perceptual talent. This is the ability to perceive multi-dimensionally. Simply put, a dyslexic can see an object mentally from many different perspectives, whether by moving their perception to different locations or by mentally manipulating and turning an object, much like rotating a 3D model in a computer to look at its other sides. Matthew, the dyslexic metal fabricator whom I interviewed just before the start of Circuit Breaker, shared that when he was creating a piece of work, he could rotate the end product in different directions in his mind. He would sometimes have an exploded view of the product where he would pull everything apart and then figure out how to fit each piece back together. Another mother whom I spoke with recently also related to me how her dyslexic daughter told her she is able to move her perception to different locations to view an object in her mind. This perceptual talent that a dyslexic possesses allows the individual to think out of the box and to see the big picture. It enhances their performance and is an asset in many occupations such as architects, designers, inventors, scientists, engineers, actors and so on. As with a dyslexic’s picture thinking style, this perceptual talent, while it is a gift, is also a source of learning problem. How so? Let’s hold our thoughts for now until we cover the last factor, and I’ll put the pieces together for you. We have heard of many famous dyslexics such as Albert Einstein, Walt Disney, Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, Lee Kuan Yew, Bill Gates, Tom Cruise, Jamie Oliver, the list goes on. While having dyslexia won’t make every dyslexic a genius, it is definitely good for the self-esteem of all dyslexics to know their minds work in the same way as the minds of these great geniuses. In the previous post, we looked at the symptoms of dyslexia. Once parents picked up some red flags that are of concern to them, the next step is to consider if you want to get your child tested.

The decision whether or not to send your child for assessment is a personal one. One of the resistance parents have is that they do not want to label their child. What I want to say is you are not labelling your child. Your child received a diagnosis and that diagnosis can open the door for you to get help, to make things easier for your child. First, let’s understand the difference between screening and assessment. Screening: - preliminary evaluation - looks at symptoms - indicates likelihood - no age criteria for screening - you can approach the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS) or use an online tool at www.testdyslexia.com (free of charge) Assessment: - thorough evaluation through information gathering - administered test for IQ, working memory, visual-spatial processing, phonological processing, etc - minimum age for assessment is 6 years old If you decide to go for an assessment, there are a few options available: - MOE’s psychologists (check with your child’s school on this) - Referral from a polyclinic, which will then direct you to KKH or NUH, depending on the child’s age - DAS, which is private but subsidized - Private psychologists. It can be an educational or a clinical psychologist. While both can administer cognitive tests, my preference is to go to an educational psychologist given the setting they work in. You can refer to the chart above for an overview of their respective scope of work Each of the above option has its pros and cons and it’ll be good if you do your own due diligence beforehand. And it is important that you seek out a psychologist that specializes in the areas you’re concerned with. The process of deriving at a diagnosis has an element of subjectivity. When I had my daughter assessed, we went to a psychologist who work in a team of 2 (most work singly), each administering different parts of the tests and thereafter reached an agreed diagnosis after taking into consideration both psychologists’ views. There are psychologists who are box-tickers and do not make further observations or gather additional information that would aid in the assessment process. This can lead to a mis-diagnosis, which some parents have shared with me from their experiences. In our next post, we will be examining the first of three factors that Ron discovered which explains how dyslexia develops, so stay tuned! In today’s post, we are going to look at the symptoms of dyslexia. Symptoms are tell tale signs that indicate possible issues one may be facing.

How do we pick up whether a child may be struggling with a learning issue? We look at the symptoms displayed by the child. We are all aware that humans have five basic senses: touch, smell, taste, sight and hearing. There are also two less known senses, which are vestibular and proprioception. The way our senses operate is that they work together to send information to the brain in order to help us make sense of our environment. When there is inaccurate input, it will lead to inaccurate output. Ron said that the symptoms of dyslexia are actually symptoms of disorientation (which I will touch on later) and affect four of our senses, namely vision, hearing, balance/coordination (which comes from the vestibular sense) and sense of time. Below is a list of some of the more common symptoms affecting each of our four senses, but they are by no means exhaustive. Vision: - shapes and sequences of letters or numbers appear changed or reversed - spelling is incorrect or inconsistent - words or lines are skipped when reading or writing - punctuation marks or capital letters are omitted, ignored or not seen - words and letters are omitted, altered or substituted while reading or writing Hearing: - some speech sounds are difficult to make - diagraphs such as ch, th and sh are mispronounced - “false” sounds are perceived - what is said does not appear to be listened to or heard Balance/Movement: - dizziness or nausea while reading - poor sense of direction - inability to sit still - difficulty with handwriting - problem with balance and coordination Time: - hyperactivity (overactive) - hypoactivity (underactive) - difficulty learning math concepts - difficulty being on time or telling time - excessive day dreaming - frequent loss of train of thought - trouble sequencing (putting things in the correct order) How many symptoms on the list did you tick off that correspond with what you see in your child? What should you do next? Who should you approach for help? What is the difference between screening and assessment? Stay tuned to our next post! I first came across this statement 10 years ago when I laid my hands on the book, The Gift of Dyslexia by Ronald D. Davis, an American who was diagnosed with autism and dyslexia. That caught my attention.

Ron went on to elaborate that “dyslexia is a product of thought, talent and a special way of reacting to the feeling of confusion.” I will be breaking down Ron’s explanations into bite-sized posts in the coming days. I hope the information will give you another perspective of looking at dyslexia and possibly direct your next step. What is dyslexia? It is a language based, specific learning difficulty that impacts reading, spelling, comprehension, handwriting (dysgraphia), math (dyscalculia) as well as balance and coordination (dyspraxia). Dyslexia has to do with the way the brain is wired. While most of us use our left brain to process languages, dyslexics use their right brain or the creative brain, which is responsible for daydreaming and imagination. Dyslexia is not due to a lack of intelligence. For a dyslexia diagnosis, a person’s IQ needs to be at least in the normal range. That said, a below average IQ may not necessarily indicate the absence of dyslexia. Ron was initially tested to have low IQ and was labelled as “uneducatably mentally retarded” at the age of 12, but was later discovered to have an extremely high IQ of 137. In other words, a person cannot be dumb and dyslexic. For a child with dyslexia, he/she is often misunderstood as being lazy, not interested in learning, not trying hard enough and/or gets distracted easily. As parents, I am sure such thoughts crossed our minds. In the next post, we will be looking at the symptoms of dyslexia. These symptoms are often red flags that alert parents to their child’s struggles. Stay tuned! |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed