|

This article was written by a Speech Language Pathologist some years back. What she described is commonly experienced by many of the dyslexics I encounter in the course of my intervention work. In addition to struggling with the English language, many of these children also struggle with the Chinese language.

As far as I know, there is no official test in Singapore for Chinese dyslexia and the diagnosis is not recognised. I agree with the author that dyslexia can occur in any language and I know for a fact that it has affected people learning other languages. Regardless of which language a child struggles with, it goes back to the root cause of confusion with symbols that exist in languages. In the case of the Chinese language, the strokes, the radicals, the high frequency words, the similarity in characters and pronunciation.

0 Comments

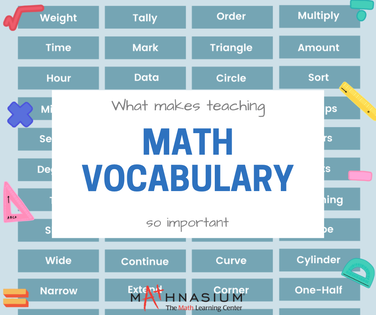

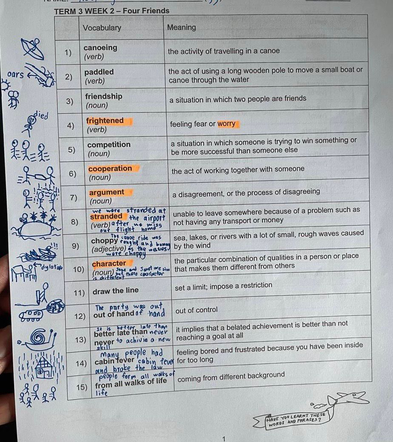

I often get parents of dyslexic children telling me that their child struggles with multiplication tables. I remember as a child, the way I learnt the multiplication tables was through rote memorising. Dyslexics, on the other hand, don’t learn the same way as we do. Multiplication tables can be mastered in a logical way and I agree with what the speaker in the video shared, through the process of first counting, then figuring out and finally, retention of facts learnt. Dyslexics are good at seeing patterns and making sense of things. Are you still making your child memorise the multiplication tables? Try a different approach if things are still not getting through for your child.  So far, I have been talking about how confusion causes dyslexia and the source of such confusion stems from symbols that dyslexics cannot picture, such as punctuation marks and high frequency words, which impact their decoding, reading fluency and comprehension. Dyslexics also encounter confusion when dealing with math subject (typically with word problems), not because they do not have the skill to do arithmetic but because they struggle to comprehend the questions. You see them re-reading the questions. Frowns start to form, fingers start tapping on the table, they start fidgeting and soon, they throw their hands in the air and give up. There are math specific vocabulary such as “remainder”, “more than”, “twice as much as” and even concepts such as “1/5”, “1/2”, “2/3” that a dyslexic struggles with. The first step to help the child is to acknowledge the child’s picture thinking style. The child needs to master not only the meaning of those specific vocabulary that confuses them, but also be able to picture and understand how fractions are represented visually. Once the confusion is replaced with certainty, things become more easeful for the child. Dyslexia is an alternative way of thinking and learning. Dyslexics have a preference for using pictures or images in their thought process rather than words. This allows them to view the world from many different perspectives and in creative ways.

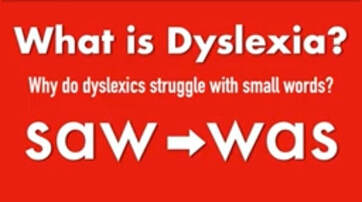

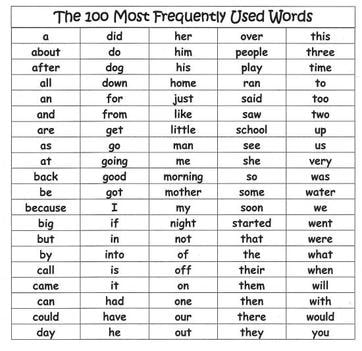

As picture thinkers, dyslexics easily become confused by things that do not make sense to their non-verbal, picture thinking style. They have fewer issues with words whose meaning they can picture, such as “dog”, “rainbow”, “dinosaur” but they often make mistakes with words like “as”, “so”, “just” in their reading. To give an example, a client I worked with identified that she could read and spell the word “as” but she doesn’t understand the meaning and hence when constructing a sentence, used it incorrectly. In order to help her master the word, she needs to create all 3 parts of the word - the meaning, the spelling and the pronunciation. One of the more commonly used meaning for the word “as” is - at the same time that. The way she captured the concept of that meaning is to make a clown and an elephant, both balancing on the ball at the same time - As the elephant balances on the ball, the clown does the same. To her, that clay model embodies her understanding of what “as” means. Once she has a way to think with a picture of the meaning of that word, the word doesn’t confuse her anymore. Besides punctuation marks (touched on in my earlier post), another source of confusion for dyslexics which impacts their reading comprehension is the common sight words, which makes up about 75% of each page of text.

Dyslexics tend to think primarily in pictures and images as opposed to words. They typically get confused by the common sight words because they cannot picture the meaning. When they cannot picture those words, they cannot make sense of what they read. They are merely mouthing the words they see in a text. A way to assess whether they know what they are reading is to get them to retell the story. Identify how many facts they can recall. Also, ask them questions (both explicit and implicit) about the passage and you will notice that they struggle to give you the correct answers, especially the implicit ones where they will need to draw an inference or they’ll give a different version from what was in the text. Very often while reading, dyslexics will also trip up on those high frequency words, either omitting, substituting or altering those words. Ron Davis, the creator of the Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme says, “if you remove the reason why a problem exits, the problem ceases to exist”. Therefore, knowing the why is critical in identifying the solutions in order to eliminate the problems. In my previous post, I wrote about how confusion causes dyslexia. To illustrate further, let’s now look at how confusion with punctuation marks, one of the symbols we encounter in languages, impacts comprehension for dyslexics.

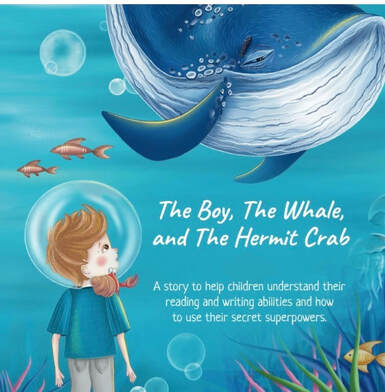

Some time back, I worked with an adult dyslexic. She is a good reader and spelling is not an issue, but she struggles to comprehend what she is reading. While she reads fluently, her reading pace was quite fast and she was not aware whenever she made reading mistakes. I then identified that she did not have a good understanding of some of the punctuation marks used. Punctuation gives meaning to what we are reading. The lack of certainty on what each punctuation mark means leaves us with uncertainty as to how to interpret the sentence read. This then gives rise to confusion. To resolve that confusion, dyslexics need to have full mastery of the punctuation marks.  There is still a lack of accurate understanding of what dyslexia is. Ron Davis, the creator of the Davis Dyslexia Correction Programme says that “dyslexia is not a complexity. It is a compound of simple factors that can be dealt with step-by-step”. Simply put, what you see your child experiencing stems from confusion. Confusion (with words, symbols, environment, etc) is what caused dyslexia. The more confused a dyslexic is, the more the dyslexic symptoms (such as letter reversal, making reading mistakes, especially with the high frequency words like ‘of’, ‘from’, ‘this’, etc) will show. Conversely, the dyslexic symptoms will diminish when the confusion is replaced with certainty. Without addressing the source of confusion, a child will continue to show inconsistency in his/her learning.  Did you know that dyslexics can think and visualise in 3D images? This perceptual talent is also one of the contributing factors to their learning difficulties. This video provides a good explanation on how this perceptual talent works and how it causes mistakes in a learning situation when it is engaged. I first met Kilian, the main character in the book early this year when I provided intervention to him. While observing how I work with Kilian, his mother, Katherine was inspired which led to her writing this children's book to help young children understand their dyslexia.

A truly inspirational book borne out of a mother's love for her dyslexic son. It captured the heart of a parent who witnessed her son's struggles with learning difficulties. More than that, it was written to bring hope and encouragement to young children, to help them understand the unique way they think and learn and to embrace their strengths to help them overcome their challenges. Colourfully illustrated with an ocean theme, it would definitely appeal to the imaginative minds of our wonderfully creative dyslexics. The book is now available on Amazon and the kindle version is free until 1 January 2024. Don't wait! Get hold of a copy to bless someone you know who needs a book like this. Edena Goh was bullied and had low self-esteem over her learning condition, but found that embracing it inspired others By any standard, Edena Goh is an accomplished student. She studied triple science in secondary school, was head pre- fect and scored seven points for her O levels. She did it all while being dyslexic. “It’s been a difficult journey,” says the articulate 18-year-old junior college student. Her mother Christina Tan, 51, says her younger daughter has al- ways had a big vocabulary. The teachers at the phonics enrichment programme she at- tended when she was around age five were impressed enough to recommend her for a grade jump, but every time Edena had to sit a reading or written test in a one-to- one setting, she threw a tantrum. Ms Tan noticed differences between Edena’s reading and writing abilities and those of her other daughter, who is 18 months older and whom she declined to name. “What she could verbalise, she could not recognise, even if they were very basic words, high frequency words, even nouns,” she says. The lawyer-turned-entrepreneur pressed for answers from the enrichment centre, childcare centre and doctors. Everyone said the girl was fine. Edena remembers that Chinese lessons during her kindergarten years were especially taxing. “I had no idea what they were saying. It was like an alien language to me,” she says. During her Primary 1 orientation, Edena was one of two children who cried as she was over- whelmed. She could not complete the activity sheets given. Ms Tan then decided to defer her formal education for a year, having realised Edena was possibly dyslexic after speaking to a psychologist friend. “Because we saw how lacking in confidence she was, we didn’t want to push her into primary school. I was really concerned about her mental well-being. That’s some- thing that will have a long-term effect,” Ms Tan says. One in 10 people worldwide have dyslexia, a lifelong learning condition that affects reading and writing. Of this group, 4 per cent have dyslexia severe enough to warrant im- mediate intervention, says Ms Sere- na Abdullah, assistant director (curriculum) in the English language and literacy division of the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS). It supports almost 4,000 pre-primary to tertiary students with dyslexia and other specific learning differences, but this is just the tip of the iceberg, she adds. Based on the Department of Statistics Singapore’s figures, there were 656,369 students enrolled in educational institutions in 2020, which suggests that an estimated 26,255 students may need dyslexia support. BULLIED IN SCHOOLEdena went for occupational therapy for a few months and had a full assessment by an educational psychologist. She also attended the Davis Reading Programme for Young Learners, a modified Davis Dyslexia Correction programme, as her mother felt phonics-based programmes had not worked. The Davis Dyslexia Correction programme was founded in the United States in 1980 by Mr Ron Davis, who developed a way to overcome his own severe dyslexia in adulthood. Ms Tan says the Davis approach believes that dyslexics are mostly picture thinkers who experience perceptual distortion – in terms of vision, hearing, time, balance and coordination – when disoriented. It teaches dyslexics how to reorient themselves using visualisation techniques as well as master high frequency words using clay to make customised “pictures” they can think with, thereby replacing confusion with certainty, she adds. However, the non-traditional approach is not widely recognised and critics have said it lacks inde- pendent evidence-based studies to back its claims. The Orton-Gillingham approach, which was founded more than 80 years ago, is more commonly used for teaching dyslexics. It is diagnostic, structured and multisensory, and uses systematic phonics instruction, says Ms Serena of DAS. Edena remembers dreading evenings when her mother would return home and drill her with assessment books and reading materials. Ms Tan admits she was strict and impatient at the time. Now, she tells parents she works with to “cut the kids some slack. It’s not that they are not trying hard enough. They are, they just need time and we need to recognise that they learn differently”. Ms Tan became a Davis method facilitator four years ago and runs Singapore Dyslexia Intervention Services. She also supports special- needs caregivers as a CareConnect champion under CaringSG, an initiative for the special needs community. A year later, Edena was back in school, this time with the ability to read a book during silent reading time – using a ruler so she would not skip lines. But her struggles with learning brought on unwanted attention in the form of bullying. “I used to be called ‘stupid’ for not being able to learn Chinese and for being a slow- er learner than my peers. I think that lowered my self-confidence. Since then, even with a decent PSLE score, I carried this burden of not being good enough,” says Edena, who had a score of 237 and was exempted from Mother Tongue. Ms Tan says that while her daughter was a slower learner in the beginning, she is a “big picture thinker” like many dyslexics she has seen in her practice. Edena easily grasps concepts and thinks out of the box, which has helped her excel in school. Her condition still flares up during stressful times such as examinations, when she gets “a bit disoriented sometimes”. But she says: “My parents have always encouraged me to just do my best. That helps to ease my anxiety as well, thinking that I don’t have to be the best – I just have to do my personal best.” EMBRACING HER GIFTStill, dyslexia was not something she volunteered to share with her class- mates. The turning point came in Secondary 3, when she organised a camp for school leaders. During the camp, participants shared their insecurities and realised it was all right for leaders to have weaknesses as long as they sup- ported one another. Edena says: “Whenever I share about being dyslexic with others, most of the reactions I get are those of shock because they see that I’m doing well. It encourages me even further that others draw inspiration from me.” As she embraced her condition, her dreams grew larger. Edena was one of eight finalists in the Halogen Foundation’s National Young Lead- er Award 2020. The foundation is a charity that nurtures young leaders. If she could, she would aim for the stars. Her eyes light up as she shares that her “ultimate dream” is to be an astronaut. She also hopes to be an engineer as she enjoys robotics. “Entering a male-dominated industry is something that is very empowering. And I think that follows my story of trying to inspire other people,” she says. Looking back on her journey, she says: “Although it was a tough journey, struggling with all this self- doubt, I wouldn’t change anything.” But she says she hopes that dyslexic kids starting Primary 1 in 2023 “won’t feel so insufficient and insecure about themselves”. “You are special, even though you do not realise it now.” PREPARING YOUR DYSLEXIC CHILD FOR PRIMARY 1GET HELP EARLY

Starting primary school can be a source of anxiety and stress as dyslexic children navigate a new environment and get used to new expectations, says Ms Serena Abdullah from the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS). She says “a lot is required of a child even at Primary 1. Students are expected to have ac- quired emergent literacy skills and be able to read, write and spell fairly proficiently by the time they embark on their primary education”. Timely intervention, either through school- based dyslexia remediation programmes or edu- cational therapy at DAS (das.org.sg), is important. She encourages parents to set up an “eco- system of support” with their child’s school. They should also look out for challenges in literacy, behaviour, executive functioning and social skills, and seek help early. ACCEPT YOUR CHILD Many parents have a traditional view about learn- ing, which is to learn the lesson ahead of the teacher’s class, says Ms Frances Yeo, principal psychologist and programme director of Thom- son Kids Specialised Learning (www.thomsonkids.com). It is part of Thomson Medical Group and offers help for children with learning differences. This mindset does not work with dyslexic kids as their fundamental literacy skills lag behind those of their peers. “When students with learning disorders are given academic instruction that is beyond their level, they feel over- whelmed and stressed,” says Ms Yeo. Over time, this builds up and can cause every- thing from low self-esteem to thoughts of suicide. What is more important is that parents accept that their children learn differently, even though it may be hard to hear negative feedback from teachers or deal with feelings of helplessness, she adds. TRUST THAT THEY ARE TRYING “Overcoming a learning disorder is very difficult and takes time. There are no quick fixes, no medications that can make it go away,” says Ms Yeo. Parents who support their children even through the smallest of wins help them develop “a growth mindset or an internal narrative that encourages them to see learning difficulties as a challenge that they can someday overcome”, she adds. Learning is a long journey and not doing well in primary school may not be the catastrophe parents fear, she notes. “Children need space to grow physically, emotionally and academically. This also means par- ents must trust that their children are trying their best, even though the improvement in grades may not be obvious. “I feel that the hardest thing for many parents is to learn to manage their own anxieties and not project these onto their children.” Stephanie Yeo |

Categories

All

Christina TanChristina has a Diploma in Disability Studies and is a licensed Davis Facilitator. |

|

|

Professional services described as Davis™, including Davis™ Dyslexia Correction, Davis™ Symbol Mastery, Davis™ Orientation Counseling, Davis™ Attention Mastery, Davis™ Math Mastery, and Davis™ Reading Program for Young Learners may only be provided by persons who are trained and licensed as Davis Facilitators or Specialists by Davis Dyslexia Association International. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed